Until his passing in April 2016 our Chief Instructor was Peter Megann (6 Dan) who had been active in martial arts for over 40 years. During his university days he was Captain of the Oxford University Judo Club. After graduating he instructed at the University Judo Club for many years before devoting himself to Aikido from 1971 onwards; and was a dedicated student of Kanetsuka Sensei for 25 years. Peter Megann was the General Secretary of the British Aikido Federation and Chairman of the British Universities’ Aikido Federation.

Short Biography of Minoru Kanetsuka, Shihan, 8 Dan (Aikikai Foundation, Tokyo)

Born in Tokyo in 1939, Minoru Kanetsuka took up Aikido while at university (1957 – 1961) under Gozo Shioda and Masatake Fujita. In 1964 he travelled to India and then to Nepal, where he spent 6 years during which he taught Aikido to bodyguards attached to the royal household. On leaving Nepal he spent some time in Calcutta, where he taught self-defence at a police training school.

In 1971 he moved to Britain, becoming the assistant of Kazuo Chiba, who was at that time the Technical Director of the Aikikai of Great Britain (later to be renamed the British Aikido Federation). When Chiba Senseileft Britain in 1976 Kanetsuka Sensei became the Technical Director of the British Aikido Federation, and as such was delegated responsibility from the Aikikai Foundation for developing Aikido in the UK.

There is no doubt that Kanetsuka Sensei’s teaching was highly individual, though this individuality did not stem from a desire to depart from main-line Aikido so much as upon his insistence on mastering basic, orthodox Aikido principles. His emphasis is always on controlling one’s partner (i.e. attacker) with the minimum of physical force, from the very first moment of contact to final submission.

35 YEARS WITH KANETSUKA SENSEI

(Some reminiscences by Peter Megann)

I first set eyes on Kanetsuka Sensei in early 1973, when he appeared at the doorway of the Oxford University dojo. His appearance was so striking that I stared in amazement. He looked very different than he does now. Long hair, a moustache curling down from his upper lip and a goatee beard, quite massively built (I remember being struck by his muscular arms) and wearing traditional Japanese wooden geta on his feet. He looked to me like a character out of a samurai film.

What had brought him to Oxford? Well, a little background to the Oxford University Aikido Club. I had been practising Judo for quite a number of years, and after graduation I had become the instructor of the O. U. Judo Club. I had been fortunate in having as my Judo instructor in Paris someone of south-east Asian provenance, who said to me one day: you know, we should treat everyone outside of the dojo as we would treat them on the tatami: we should show them the same respect. That simple statement had a great effect on me; and in the years that followed I felt increasingly dissatisfied with Judo. There was something missing. I understood that traditional Japanese martial arts had a cultural and ‘spiritual’ dimension, but this was not much emphasized in Judo which was overly concerned, in my opinion, with winning contests. I remember being very uncomfortable when the term ‘playing’ Judo was introduced around the late 60s (How can you play at a martial art?). A French au pair girl had appeared at the Judo club in 1966 and told us she had been practising something called ‘Aikido’ in Switzerland. She asked if we would be interested in learning some Aikido at the end of our usual Judo practices. We were very happy to experience this unusual art and Annie Pochat came regularly and taught us some techniques. I was completely taken by Aikido but the time came when Annie returned home and I was bereft of a teacher.

Sometime later I met the legendary American Terry Dobson, who had come to Oxford in connection with the publishing firm of the infamous Robert Maxwell based in the city. We met once a week for Aikido practice, one to one. He was quite immense and I was particularly impressed by how gentle he was. He told me about this old and frail Aikido teacher he had in Japan, who was capable of incredible feats – this was O-Sensei – but I did not at that time appreciate the significance! But Terry returned to Japan and again I had nobody to practise Aikido with.

Then one day some years later I saw a notice at the University Sports Centre announcing the creation of an Aikido club. I eagerly went along to sign on. The club was started by an Oxford post-graduate, Phillip Harries, who had just returned from Japan, where he had taken up Aikido. He soon made contact with the Hombu representative in Britain, Chiba Sensei, who was at that time based in London, and requested some support for the newly fledged club. Chiba Sensei readily obliged. Not only did he visit the club a couple of times each term, but he arranged for some of his more senior students to come and instruct each Saturday morning. The club went from strength to strength over the next year or so, but unfortunately Philip left for further research in the US, and despite my limited Aikido experience I was obliged to act as the club instructor.

Kanetsuka Sensei came fairly regularly on Saturday mornings to take a class. Even though I was at that time at a very lowly level of Aikido, because I was the senior student after Philip left I was usually Kanetsuka Sensei’s uke. Of course, it’s a valuable experience acting as uke to such a sensei. But in those days Sensei’s Aikido was quite robust and powerful. He had studied under Shioda Sensei for seven years, then during his stay in Nepal (1965 – 1969) he had instructed the bodyguards of the royal household, and later in Calcutta he had taught at a police training school. Then when he came to England he became assistant to Kazuo Chiba, who is famous (or should one say notorious?) for saying that the dojo was a battlefield and Aikido was a matter of life and death.

I remember I was a bit apprehensive when the technique he was demonstrating was hanmi handachi shiho-nage (very fast and tight! – and as with all his techniques it was quite impossible to escape) and even more scary was juji-garame-nage! But I survived. Kanetsuka Sensei eventually moved from London to take up residence in the quiet Oxford suburb of Iffley Village. I remember occasions when he hosted dinner parties for Aikido students at his home, when the ‘Mongolian pot’ was prominent. There would be piles of raw vegetables prepared and we would cook them in the boiling water that surrounded a central chimney stack, emptying them on top of rice or noodles. It was a very sociable meal. Of course, Kanetsuka Sensei was an adept cook: he had run a restaurant in Kathmandu for a number of years.

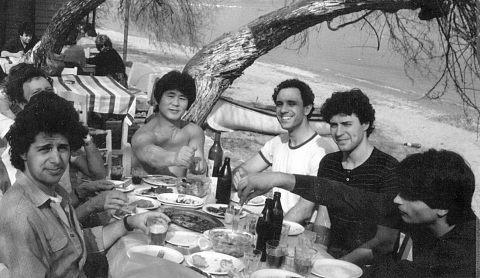

Besides taking weekend courses all over the UK, Kanetsuka Sensei had numerous engagements abroad, and I had the great good fortune of being able to attend many of these: in Belgium, France, Spain, Morocco, Poland, Sweden, Greece and Turkey. Sensei got on tremendously well with everyone: he took a real interest in people and greatly enjoyed socializing. I remember a course in Brussels when he suddenly recognized someone he hadn’t seen for some years. He called out her name (he has always had a fantastic memory for people’s names) and said “I didn’t recognize you. You used to have long hair”.

Once in Athens when he was conducting a grading examination, he asked the candidates their names. There was the usual Spiro, Kostas, Mihalis. Then he asked another student. “Anaximander “(the noble name of a 6th century BC Greek philosopher) was the reply. Sensei found it a bit difficult to get his tongue around that one! Talking of Athens, where he gave courses every year at Easter time, I remember one of the Greek students telling me that one time when Sensei was having a meal with a group of them, he insisted on having raw eggs over the pilaf. Of course raw eggs with rice is quite usual in Japan, but it is not something which appeals to Greeks and they felt almost physically sick in eating it, though they could not reveal this to him.

Kanetsuka Sensei always appreciated food of any nationality. Once Matthew Holland and I were with him in Madrid on the occasion of a European Aikido Federation congress. One evening we were walking along a street when he suddenly exclaimed ‘I can smell garlic prawns (gambas al ajillo). I had them somewhere around here a few years ago and they were fantastic’. He followed his nose and we soon came to a tapa. It was the same one where he had eaten them before…and the owner recognized him and gave him a warm welcome.

Kanetsuka Sensei always showed a great responsibility for his students. In 1985 a number of BAF students accompanied him to Düsseldorf to attend a big course to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the German Aikido Federation. The former Doshu, Kisshomaru Ueshiba was there, and numerous other celebrated Japanese sensei. At the end of the course there was an announcement in German which we didn’t understand. Other students were being directed here and there, and eventually our group found itself abandoned with no idea where we were going to spend the night. Sensei came over to us, and when he learnt of our plight he was very concerned. Soon he found a couple of sympathetic German students to whom he explained our predicament. They offered us accommodation at their house near Cologne (about an hour’s drive away). Kanetsuka Sensei insisted on coming with us, even though accommodation was reserved for him at a hotel in Düsseldorf with the other Japanese sensei. The German students found this quite extraordinary. I think they could not believe that their sensei would show such concern for his students.

While Kanetsuka Sensei was living in London, Sekiya Sensei came to stay with him for a year. I believe that this had a profound influence on the development of Kanetsuka Sensei’s Aikido. Sekiya Sensei, then in his sixties and of quite frail build, had been studying under Yamaguchi Sensei for many years. I remember that one particular term began to crop up: atari. This means something like ‘to hit the mark’, ‘to catch’ (as in catching a fish with a line or rod). As I understand it, in Aikido it means taking control of your partner at the first instance of contact. This contact is first made through the point of contact – through the wrist, for example, with kata-te dori. This can only be achieved with completely relaxed shoulders and arms, but with a strong centre. The strength of your centre must radiate through your relaxed upper body.

Sekiya Sensei introduced Kanetsuka Sensei to the traditional Japanese sword school of Kashima-shin-ryu, which he had studied under Yamaguchi Sensei. The action of the body in Kashima is very relaxed, though your centre is filled with energy and you posture is low and strong.

A few years later Kanetsuka Sensei moved with his family to Oxford. He established his own dojo in the Iffley Village hall, and started classes based on kashima. These were quite hard work. The first two thirds of the classes were concerned with sword-work. The bokken used for kashima are much more robust and heavy than the normal kata-bokken. They have to be, since kashima entails the direct, forceful striking of uke’s bokken. The degree of concentration is considerable. The last third of the lesson was the practice of Aikido based on the principles of kashima swordwork … on a solid wooden floor. One’s ukemi improved no end!

In 1986 my destiny and that of Kanetsuka Sensei converged. Throughout the summer of that year Sensei suffered severe headaches and fainted several times – once during Summer School, which caused a good deal of consternation. Despite various examinations and tests the cause of the problem remained a mystery and he continued his exacting programme of daily teaching in London and Oxford. At the beginning of the year I had suffered a ‘cardiac incident’ and was rushed to the John Radcliffe hospital in Oxford. While I was lying in a cubicle waiting to be examined I heard a voice that I recognized saying ‘Peter Megann, what are you doing here?’ It was Kim Jobst. He had been one of my Aikido students while studying medicine at Oxford University. After graduating he had moved to London to continue his medical studies and had continued Aikido under Kanetsuka Sensei. To cut a long story short, I went for a check-up at the hospital later in the year and my consultant was Kim. He asked about Kanetsuka Sensei and I told him about Sensei’s problem. Kim was concerned and decided to visit Sensei in Iffley, where he gave him a thorough examination and suggested that Sensei request that he should be transferred from his doctor to his own care.

One Saturday a little while after, I returned home around noon and my wife told me that Sensei had phoned to say that he was in a bad condition. I rushed round to his house (his wife was away and he was alone), and I saw that he really was very unwell. I decided not to waste time and I drove him to the casualty department of the John Radcliffe Hospital and he was admitted immediately for an examination. While a doctor was examining him, Kim Jobst entered the examination room and was quite annoyed. “Why did you bring Sensei in today?” he asked. “It’s not my day to be on duty here”. “Kim, I had no choice,” I said. “Sensei was really in a bad way”. Happily, Kim managed to arrange that he would be in charge of Sensei while he was kept in and various tests would be carried out.

About a week later Kim phoned me and broke the bad news. It had been discovered that Kanetsuka Sensei had a massive cancer in the laryngo-pharyngeal region (the upper nose behind the throat). It was surprising that it could have escaped detection for so long and was now far advanced. Kim asked me to come into the hospital that evening and be present when they broke the news to him. I recount all this because it casts a light on Sensei’s strength of character and his continuing concern for his students. When Kim explained the situation to Sensei and indicated that the outlook for his recovery was not good, Sensei took it very calmly – stoically, you might say. Then he said to Kim “Kim, you look very tired. When I get better I’ll give you some shiatsu (Sensei was very proficient at shiatsu and had even given shiatsu treatment to the late Doshu)”.

The cancer was too near to vital arteries to permit surgery and in the weeks that followed Kanetsuka Sensei underwent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. He realized that the heavy doses of morphine that he was being given to cope with the pain were upsetting his digestive system. He was certain that it was vital that his digestive system at least was working properly and so he chose not to take morphine, even though this meant tolerating a constant acute headache. He had great faith in carrot juice and made his own juice in large quantities. Whereas the visitors of other patients received the traditional grapes and chocolates, Sensei received sacks of carrots! After a week or so his face was glowing – though there was perhaps a rather orange look about it.

I remember visiting him one day and thinking to occupy his mind I started to discuss ikkyo with him. I asked him about the timing of the initial shomen attack of the irimi version. He whispered hoarsely “Make shomen”. He was lying on the top bed of a twin-bed unit. I made a shomen-uchi attack, and the next moment I found myself on the floor besides the bed. He had lost none of his speed and vigour!

When he was dismissed from hospital and returned home, Sensei took over his own destiny with great determination. Diet, he believed, offered the best chances of survival. He became 100% vegetarian, drank copious amounts of carrot and beetroot juice, and followed a Japanese traditional regime of herbs. As soon as he had recovered some of his strength he resumed Aikido practice. He was so thin that his keikogi swamped him and so he resorted to wearing a tracksuit. With his shiny bald head (as a result of the chemotherapy), he looked like a Buddhist monk.

In late 1986, as BAF General Secretary, I was faced with a big dilemma. Earlier in the year, Kanetsuka Sensei had been booked to conduct a weekend course in Lille in Northern France, and I was asked to confirm that he would take it. Would he be strong enough to undertake such a strenuous undertaking, I wondered. Should I suggest cancelling the engagement? I contacted Mr. Yuzuru Mizuno, the managing director of Panasonic Finance UK. Not only was he evidently highly qualified in financial matters but he was also an Aikikai 5 Dan.

When I phoned him and explained the situation he immediately agreed to come to Lille and help out if necessary. At all events he would drive us to Lille. Because of a delay on the way to Dover we missed the 10pm sailing and had to wait in a cold and draughty waiting room for the midnight ferry. I remember marvelling that despite the discomfort Kanetsuka Sensei didn’t utter a word of complaint. We eventually reached our destination about 4 o’clock in the morning. Could Kanetsuka really manage to take the course that started at 10am? He looked dreadfully weak and tired.

At about 9.30am I knocked at Sensei’s door. There being no response, I tried the handle and it was not locked so I opened the door to go in. There was a bang, and when the door was open there was Kanetsuka Sensei unconscious on the floor behind the door. I was distraught: what had I done to Sensei? Happily he soon came to. I suppose that the door had struck him on the leg and in his weakened state the shock had caused him to faint. Fortunately, Mr. Mizuno offered to take the first session. After a few more hours’ sleep Kanetsuka Sensei was ready for action and gave a revelatory demonstration of how, essentially, Aikido did not depend on physical strength. I recall him effortlessly dealing with a particularly large and fit young Frenchman, who was a P.E. instructor.How prophetic had been the advice that Sekiya Sensei had given him all those years before. After observing him practice with his customary vigour Sekiya Sensei had remarked “No, no, Kanetsuka-san. When you become my age it will be impossible for you to practice like this”.

It has been an immense privilege for me to follow Kanetsuka Sensei’s development over all these years. I say ‘development’ because his Aikido is being ever refined, even though the basic elements remain the same: the principles of tori-fune and furi-tama, of performing zarei, (kneeling bow), of the makko-ho stretching exercises which he includes in every class. He says that the dojo is his laboratory and he shares his discoveries with us his students. We are very lucky to be part of this process.

To return to my quest for another dimension to a martial art, which I mentioned at the start of this article, I certainly found it in Kanetsuka Sensei’s teaching. He has always emphasized the values of traditional Japanese martial arts. Correctness of behaviour and respect for the dojo and everyone using it has been tantamount. This starts at the entrance of the dojo.

Whereas other martial arts groups using our dojo cast their footwear in no order around the entrance, the Aikido footwear is always neatly lined up outside the dojo. Sensei recounts that he was present when Robert Kennedy visited Shioda Sensei’s dojo in Tokyo in 1962. He took it upon himself to place the senator’s shoes tidily at the entrance of the dojo. He can spot an incorrectly tied belt from 30 yards! And he checks that at the end of the practice everyone is sitting upright in seiza, with straight backs, and with their jackets properly adjusted so that no bare chest is exposed.

Of course, all this is routine in the BAF and we take it for granted; but that is because Kanetsuka Sensei (and Chiba Sensei before him) insisted on these things. One particular remark which I heard him make struck me as particularly unique and enlightened: in Aikido, in our defence against an attack, we must avoid being injured ourselves and avoid injuring the attacker. That has become a key feature of Kanetsuka Sensei’s Aikido.